Description

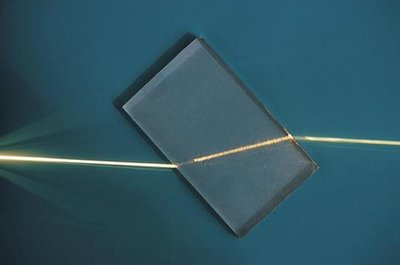

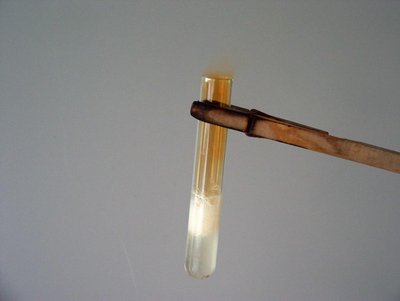

Thin-film interference is a natural phenomenon in which light waves reflected by the upper and lower boundaries of a thin film interfere with one another, either enhancing or reducing the reflected light. When the thickness of the film is an odd multiple of one quarter-wavelength of the light on it, the reflected waves from both surfaces interfere to cancel each other (assuming the refractive index of the thin film has a value between the refractive indices of the materials above and below it). Since the wave cannot be reflected, it is completely transmitted instead. When the thickness is a multiple of a half-wavelength of the light, the two reflected waves reinforce each other, increasing the reflection and reducing the transmission. Thus when white light, which consists of a range of wavelengths, is incident on the film, certain wavelengths (colors) are intensified while others are attenuated. Thin-film interference explains the multiple colors seen in light reflected from soap bubbles and oil films on water. It is also the mechanism behind the action of antireflection coatings used on glasses and camera lenses. If the thickness of the film is much larger than the coherence length of the incident light, then the interference pattern will be washed out due to the linewidth of the light source.

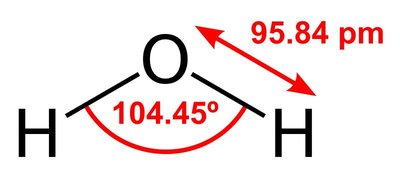

The true thickness of the film depends on both its refractive index and on the angle of incidence of the light. The speed of light is slower in a higher- index medium; thus a film is manufactured in proportion to the wavelength as it passes through the film. At a normal angle of incidence, the thickness will typically be a quarter or half multiple of the center wavelength, but at an oblique angle of incidence, the thickness will be equal to the cosine of the angle at the quarter or half-wavelength positions, which accounts for the changing colors as the viewing angle changes. (For any certain thickness, the color will shift from a shorter to a longer wavelength as the angle changes from normal to oblique.) This constructive/destructive interference produces narrow reflection/transmission bandwidths, so the observed colors are rarely separate wavelengths, such as produced by a diffraction grating or prism, but a mixture of various wavelengths absent of others in the spectrum. Therefore, the colors observed are rarely those of the rainbow, but browns, golds, turquoises, teals, bright blues, purples, and magentas. Studying the light reflected or transmitted by a thin film can reveal information about the thickness of the film or the effective refractive index of the film medium. Thin films have many commercial applications including anti-reflection coatings, mirrors, and optical filters.

Thin-Film Interference News

Collections

No collections available for this topic.